Castleton Tower – 5/17/2013

I know this is long, but to write a short trip report on such an excellent, mentally-and-physically challenging day wouldn’t do it justice.

TL; DR: This was my and Christian’s first desert tower and first true multi-pitch trad rock climb. It was wild.

fBack in February, Christian and I made plans to go on a spring trip. We wanted to get off the map, go climbing, and have some hiking adventures. We stuck to our plans, and before I knew it I was stuffing a bag full of gear into an airplane baggage compartment. We flew into Salt Lake City on Thursday the 16th, crashed at Christian’s friend’s place in Provo, and the next morning woke up at 4am to drive to Moab and climb.

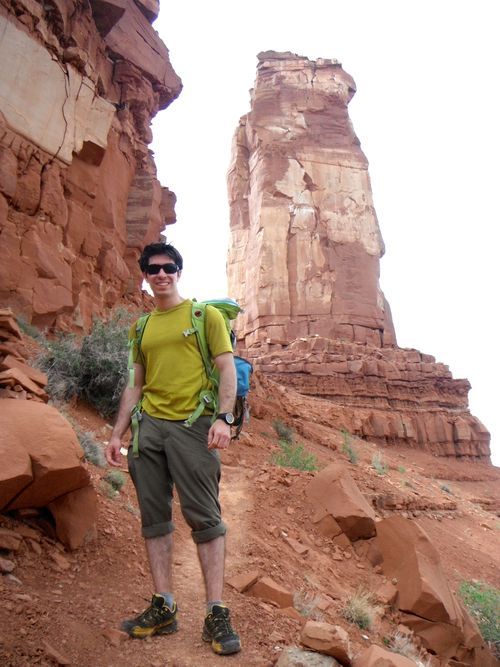

We arrived at the base of Castleton tower and hit the trail by 9:30am. The tower loomed above the trailhead like a silent, massive obelisk. As you hike up to it, it becomes more and more difficult to imagine just how huge of a timescale it takes to create such a geological structure. Its presence and dominance matches up pretty well with the timeless Mallory quote.

Why climb Castleton? “Because it’s there.”

A second, equally appropriate response that was going through my head on the hike up would also be: “Because it scares the crap out of me.”

Castleton Tower is a 400-foot iconic desert tower slightly northeast of Moab. It sits on a 1,000 foot pedestal of sandstone talus and dirt, standing guard over Castle Valley. With a summit elevation of 6,656 feet, it provides spectacular views of the valley and a few other formations that I want to come back to: the Priest and Rectory, and Sister Superior. It was first climbed in 1961 by Huntley Ingalls and Layton Kor, and the route is listed as one of the top 50 classic climbs in the US. The rock is calcite-covered Wingate sandstone. This means strong, secure feeling, orange rock, but the white, streaky calcite surface makes it slippery—like polished cobblestones of old European streets. The climb splits into four trad sections with bolted belay ledges plus 3 bolts protecting the crux third pitch.

I led the first pitch, which was straight forward with reasonable protection up two chimneys. The first squeeze chimney was quite an experience. Squeezing and forcing myself up between two slick calcite walls to a chock stone made me wonder what we were getting into. It was awkward climbing—pushing against the two walls and using my whole body to smear and jam myself up. This pitch is rated 5.6, but I felt it was 5.7ish because of my lack of experience with chimney techniques and some problem solving in how to get up efficiently. However, the hardest part of this pitch for me wasn’t the physical moves, but the mental acceptance that we were here, on this tower, and at its mercy. It was crucial to know that keeping a level head and making right decisions would mean a safe, well protected, and memorable climb. Equally as important was understanding when to turn around and how to constantly communicate.

Christian led pitch two, an adventure up a vertical crack system with some spicy holds and foot work. We both struggled up this one a bit, as the cracks were too wide for good hand/fist jams, and the holds not quite secure enough to pseudo-face climb. Protection options were decent, but some of the wider sections were a little tough because of the slippery calcite. It’s not a comforting feeling when a number 4 walks in what would otherwise be an excellent placement. It was comforting, however, knowing that it was that same number 4 that stopped Christian’s fall.

Three fourths of the way up the pitch, after stemming and face climbing, moving from the left most crack to one of the twin cracks, Christian slipped on some thin holds. The well placed pro and quick catch led to a rest and a finished pitch shortly after. In retrospect, I think we were really objective about our first trad leader fall. The gear held, the communication was good, and as quickly as it happened, Christian was back on his way to finish the pitch. It was all business. P2 was a hard and sustained 5.8, exactly as advertised, and I think we were both really happy when it was over.

I led pitch three, the crux pitch. It was awesome the first time up (more on that later).

It starts out as another off-width squeeze chimney. I found a shoddy placement for a number four in the back of the start of the chimney, and was relieved at an excellent slung chockstone and bolt to protect the first section. Past the first bolt, some tricky face climbing and stemming kept me moving up inside the chimney. I clipped and passed the second bolt until I got right underneath the third and final bolt that protects the crux. I immediately understood why this was the crux pitch and the hardest section of P3…

The chimney narrows to be too thin and awkward for me to squeeze and push myself up, and instead required one of two options, both requiring leaving the comfort and perceived safety of the chimney. The first was very thin and committing face climbing on calcite. The second was equally committing layback and stemming moves to get up and past the crux to a jug on the face. Laybacking the moves worked best for me, as I leaned out with 300 feet of air underneath my back, and tried to choose the least calcite-covered parts of the wall for something resembling grip for my feet. I failed the first time, falling back down below the bolt as my feet slipped off. I can’t say this enough—that there are bolts protecting the crux is amazing.

The second time, I somehow willed myself up to the jug, laybacking up over the crux, seemingly flexing every muscle in my body to hold on to the edge of the crack and move up to a thin face hold that provided some stability and security to get to the jug just above. Carefully smearing my feet on calcite covered dimes and chips, and through clenched teeth, I moved up to the crimp. My muscles and lungs seemed to exhale the same air of relief when my fingers curled around the next reach, a positive calcite-covered hand hold, which I used to pull myself up to a rest point.

Once up past the crux, I squeezed myself back into the offwidth. At this point I realized that I face-climbed higher than I wanted and the bolt was a good 10 feet below me. To get to the thin finger crack in the back of the offwidth to place protection, I had to drop down the chimney a few feet to get close enough to the crack. It’s awkward enough to squeeze and work your way up a tight chimney. Slowly lowering yourself without taking a 20 foot whipper was even less fun. A couple small nuts and a #1 Metolious cam worked excellently in the crack in back of the offwidth, and I was able to rest a bit in the chimney while a group above us started up the fourth pitch. P3 was a 5.9 at minimum, and it made you earn it—both mentally and physically.

Once there was room on the ledge, I finally topped out, built anchor and started to bring up Christian. Shouting down what I did to move through the crux, I was realizing how much this pitch is not done by a formula. I feel that it is defined entirely by what works for each individual climber, and no matter what beta might be given to get through it, it’ll always be easier said than done. That seemed to be a secondary theme to our climb: easier said than done.

We rested at the top of pitch three, glad that it was finished, but it was pitch four where some trials and tribulations started on our climb. Throughout the day we were getting some pretty strong gusts of wind, but inside the chimneys we were more or less protected. At the top of the third pitch you’re anchored into a nice ledge that was directly exposed to the wind, which was gusting up to 30mph and staying sustained at about 20mph.

Christian led the pitch, and about halfway through we ran into rope-drag issues as the rope kept getting caught in a chockstone. After repeated trades of “Slack!” or “Take!” with not much happening as I fed and pulled in rope, Christian set up a few more bomber cams and I lowered him down above the chalkstone.

After not being able to reroute the rope to avoid the chock, he set up a gear anchor and belayed me up so that we could avoid the drag delays and finish the route. By this point we had both been hammered by the sustained winds and were pretty tired and cold. My mind and body, already tired from 350 vertical feet of continuous focus on climbing, were becoming worn from the constant cold air. It didn’t help that the new belay spot was in another chimney which created a corridor to accelerate the wind through.

I was hunched over in a t-shirt and climbing pants, belaying and freezing, realizing that climbing and mountaineering is a miserable endeavor with rewards that are very difficult to explain or measure. “Because it’s there…” — what does that even mean?

I paused my thoughts of misery and Why-The-Hell-Am-I-Freezing-On-This-God-Damned-Desert-Tower when I paid out a bit more slack to Christian as he reached the anchors. He pulled up the remaining rope and put me on belay, and as I deconstructed the anchor and started climbing, those thoughts subsided.

A very fun and much needed hand traverse woke my wind-battered muscles up. Concentration on continuous movement as well as finding the foot placements and body balance to keep moving had relit the spark that keeps me so excited about climbing. As I climbed and cleaned the route, my reinvigorated focus led me to the anchors and then the summit, where it dawned on me that we climbed to the top of one of southern Utah’s most iconic towers via one of the country’s most iconic climbing routes.

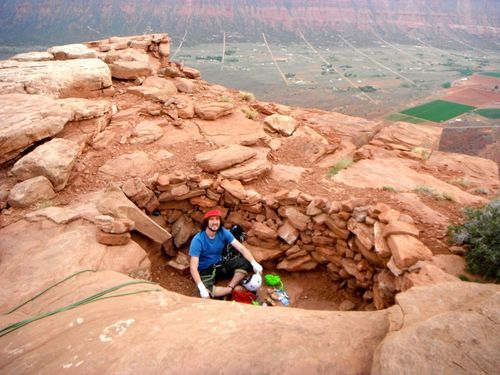

At the top, we dropped into a protected bivy spot to shield ourselves from the wind’s onslaught. We looked through the summit register, snapped photos, and ate some much-needed snacks, all the while starting to talk about the climb and stopping mid-sentence—always saving the thought for later, after we got down.

Weeks of looking through trip reports and getting myself psyched-out on the climb came down to chewing on a Clif bar, smiling at the gorgeous summit views of Castle Valley and the La Sal mountains, and thinking to myself: “No one mentioned the wind!”

We savored the moment a bit longer and then got ready to rappel down the route since we only brought one rope and there weren’t other groups coming up. We rappelled from the summit to the top of the third pitch and then down to the top of the second pitch without issues. At the top of P2, we anchored in and started to pull the rope down.

As we pulled the rope, its weight took over and made pulling it down easier. The midpoint of the rope arrived, then a few more feet, and then no sooner did Christian yell “ROPE!” to no one in particular than did the whole process suddenly come to a halt. The wind was as loud as ever, but the idea that our rope was stuck somewhere on the third pitch brought an uneasy silence over the two of us.

“It’s stuck. The rope is stuck.”

Some seconds passed, mixed in with expletives and thinking out loud, but it dawned on both of us that we’d have to climb up to at least assess the situation, and hopefully free the rope from wherever it was.

“I’ll lead it.”

We’re both tired, and the situation is dispiriting. The plan was for me to re-climb the third pitch, and hope that the rope was stuck close to us. I’d then leave a bail carabiner on one of the bolts and be lowered back down to the top of pitch 2, where we’d continue our descent.

Barely reorganizing the rack, we trade gear, double check our belay, and I head up. I’m not sure if my heart was racing or I felt that the sun was a bit lower than where I’d want it to be, but I felt a need to hurry up the pitch. I tried hard to remember exactly what and how I placed gear the first time, exactly where and how I placed my limbs. As the stress and faint muscle memory took over, I found myself past the chockstone, past the first bolt, and as I got to the 2nd bolt and looked up into the offwidth, my heart sank into my stomach.

Christian later said that it was at that moment, when I was shouting down to him, that he first heard some frustration and emotion in my voice.

“It’s stuck above the crux. I have to climb the fucking crux again!”

The rope was caught in a chockstone about 8 feet or so above the crux, almost exactly where I started to re-enter the offwidth the first time up.

I squeezed up to right below the last bolt and clipped the bail biner on. After I clipped my rope in and rested, I decided to try and save some energy and see if I could attempt some sort of aid-layback-face-climbing awkward techniques to get up far enough past the crux to loosen the rope.

The struggle that ensued involved trying to use slings to aid on the bolt and failing, then using my daisy on the bolt with combination of the slings and also failing. Each time involved pulling and stepping up on the sling, trying to grip anything on the calcite covered-edge of the chimney to stabilize myself, and then falling back down. The bright side to this miserable pattern was that the falls were clean. A lot of “TAKE!” and “OK! READY? GOING FOR IT!” was shouted to Christian, and a lot of expletives were shouted to no one in particular.

At one point, I rested and took a second to notice that a couple cuts on my fingers had covered the wall, slings, and rope with blood. Castleton wasn’t letting us go that easy, after all.

I decided to try and layback the crux as I did in the beginning, and to stop attempting the failing aid nonsense that was doing nothing but exhausting my energy. Once again, the first attempt failed—a couple feet above the bolt I couldn’t hold the layback, my feet slipped out, and I dropped down to stare back at the wall—now covered in dried blood in addition to the mocking streaks of calcite. I was tired, hungry, and frustrated. I needed to get the rope down. I could see exactly how it was stuck, and I just needed to get past this one section.

Somehow, I made it up. I don’t know exactly what strength I got to propel me up, what I screamed into the wind, or where I placed my feet or hands, but somehow the cards fell into place. I might have felt some sort of elation when I finally reached that safe and now-generous face hold, but whatever it was it was quickly overshadowed by the type of exhaustion and focus that comes to you when you’re trying to desperately get yourself out of a dangerous situation. I’m not sure how I got through that crux the second time, but I’m sure that “desperately” would be a good way to describe it.

Squeezing myself back into the offwidth, I reached the rope and whipped it off the chalk stone. I then grabbed the daisy and sling that were still connected to the bail carabiner on the bolt, and lowered myself down until the tension was back on the rope. Christian lowered me down as I cleaned the gear out on the way down.

The last two rappels were without incident, thankfully, but both Christian and I were on edge as the sky was getting a bit darker, the wind a little colder, and we were that much more hesitant at each time we pulled the rope. We opted to go down the cleanest parts of the faces so that the rope would drop down with the least risk of getting caught, and we tried to wait for the moments of the least wind as we dropped and pulled our rope. As we down-climbed the last fourth class section and found ourselves on the base of the tower, I didn’t want to let the experience truly sink in yet—we still had a windy, sandy trail left between us and the car.

We hiked through the talus, rounding corners where sustained winds almost knocked us off our feet and down the sandy set of cliffs below. Making our way down the switch backs, we once again found ourselves starting to put our thoughts into words, only stopping mid-sentence—we weren’t quite home yet. A few more steps were needed for celebration.

As the sky turned a darker shade of blue and then sun hid behind a thick evening layer of clouds, Castleton transformed from the sun-lit orange icon to a darker, more menacing tower than the one we’d seen on our approach in. We had summited, and it wasn’t happy about it. Its shadow seemed to spread the evening over the valley, and I found myself caught in between elation of a successful climb and the awareness of my own fragility.

As the trail mellowed, however, our exhaustion began to be mixed with a bit more laughter, and our spirits rose as we hiked closer to the car. At the trailhead we recapped our experience to a couple climbers who were setting up camp for the night. Not bothering to reorganize any gear as we tossed it in the trunk, we got in the car and drove off. Castleton Tower was now a looming black silhouette behind us. Sleep and the rest of our weekend in Moab were waiting.

Pictures:

At the start of the trail. High spirits!

Myself near the base of Castleton

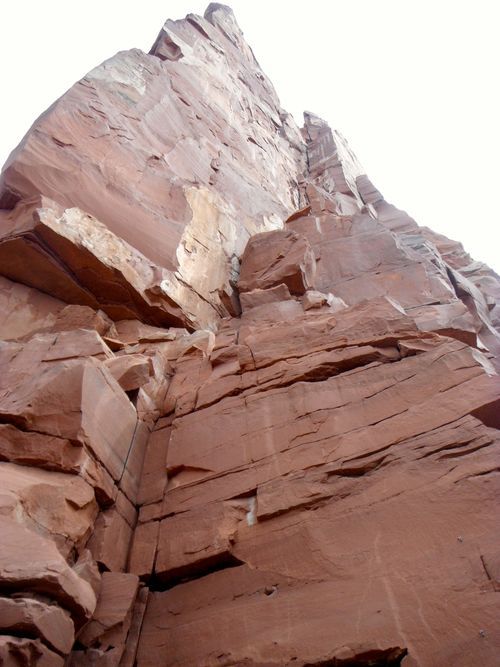

Kor-Ingalls Route follows the chimney systems all the way up.

Geared up, ready to head up.

Looking up the second calcite covered Chimney on P1

Christian topping out at P1

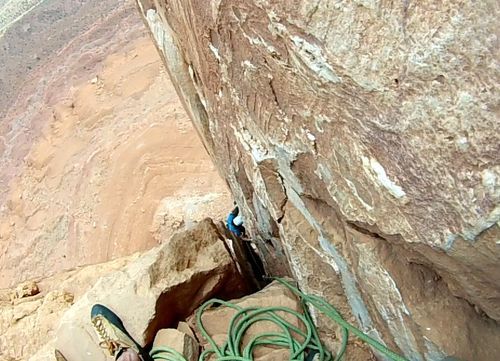

Christian leading P2. You can see him near the center of the photo.

Looking down while going up P2.

Christian stemming and face-climbing just above the crux on P3, about to reenter the off-width chimney.

The awesome hand traverse on P4.

Summit Bivy spot!

Self-shots on the windy summit, before the real adventure starts.

Castle Valley and the La Sals from the Summit

—-

Reaction:

In retrospect, this trip was a lot of firsts and a staunch mental challenge. Physically, everything on those four pitches was well within our abilities. Both Christian and I are fit and competent climbers, having spent the months leading up to our trip going climbing together multiple times a week.

We were comfortable leading, placing and retrieving gear, setting up anchor, and communicating. Our trip last summer to summit Liberty Bell in the North Cascades gave us experience in exposed pitches and sparse protection. We didn’t lead that climb though—and when you’re seconding on a trad climb your mind isn’t getting stretched across so many decision points: where’s the route, how to climb, where to place gear, which piece to place, where to take breaks, where to make anchor, how far above my last piece am I, what’s the weather doing, what’s the rock quality like, can my second get up the route I chose, etc., etc., etc.

Woulda-coulda-shoulda:

- Started earlier somehow

- Did less waiting/watching behind the group above us

- Brought two ropes instead of one and rappelled down the north face

- Recorded more video of the route!!! (and checked to see that the second half of my memory card actually made it onto my hard drive. Unfortunately, it didn’t.)

- Brought along a puffy and headlamps in our haul bag—we really don’t have an excuse for not bringing these essentials, especially when we bring them on every other trip.

Lessons Learned:

Positives:

- Chose a great route that was definitely within our abilities (though we were pushed)

- Excellent communication and team work, as well as pushing each other up the route

- We each led the routes that played to our strengths. I’m really glad we split it up the way we did.

- The folks who have built the trail leading up to Castleton are amazing. The trail is in great condition and its great not having to do any route finding on the approach.

Next time:

- The forecast called for a windy, gusty day with 15-30mph winds. Up top was surely even more affected by those strong winds. We made a good judgment call to consider that doable, and I do think that if the winds were forecasted to be much worse we wouldn’t have gone up. Though I was freezing, I didn’t feel unsafe due to the wind.

- Less gear! We brought up a full rack of doubles from fingers to hands and definitely didn’t use much of our rack. Some key doubles in #.75s, #1s, #3s, and nuts were key, however.

Reinforced:

- Getting to the summit is only half the route. With our rappel adventures it took us a solid extra couple hours to get down. You’re not home safe until you’re off the mountain. Always.

Last thoughts/A caveat:

I don’t want to put off any trad climbers by giving them the impression that this tower was extremely difficult. There’s definitely a reason that on MountainProject and other trip reports you’ll find folks saying “overrated” and others saying “5.10 R!!!!!!” Thousands have reached the summit of Castleton, many of them on the K-I route. Overall, this climb was fantastic, and totally doable by those comfortable leading trad at a 5.9/10 level.

I tried to make the trip report dramatic enough to reflect the stress and challenge that Christian and I faced on that day, because we certainly were challenged and exhausted by the adventure. At no point however, did I feel that we were in danger for our lives or facing a point in which we were running out of options. Even in the exhausting re-climb of the third pitch, we always had backup/bail options in place and available.

Lastly, and everyone who might read this already knows this, but climbing is inherently dangerous. Even more so when you factor in complacency. Trip reports, forums, and YouTube videos don’t make up for experience, which is another reason I’m so happy with this trip: it provided myself and Christian even more experience to start leading some of the classic routes up here in WA.

I’m excited for the next adventure.

-Ely